Yerkes-Dodson: Lore, not Law

Cover image by Fathromi Ramdlon on Pixabay

By Cindy Nebel

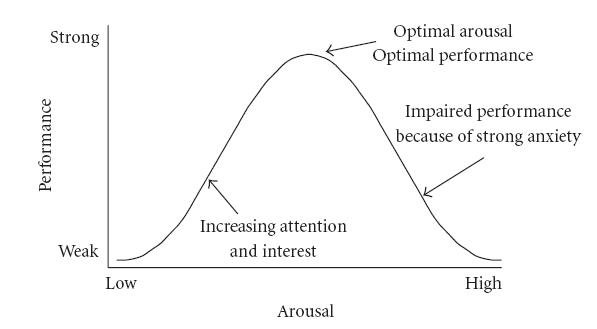

In 1908, Robert Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson published a study that would change our understanding of the complex relationship between stress/arousal and performance (1). Commonly referred to as the Yerkes-Dodson law, what they found was that as stress increases, so does performance, but only up to a point. If stress becomes too high, performance begins to decrease.

Image source: Diamond D.M., et al. (2007). "The Temporal Dynamics Model of Emotional Memory Processing: A Synthesis on the Neurobiological Basis of Stress-Induced Amnesia, Flashbulb and Traumatic Memories, and the Yerkes-Dodson Law". Neural Plasticity: 33. doi:10.1155/2007/60803.

The Yerkes-Dodson law is used frequently in performance settings. It is talked about in the Harvard Business Review, verywellmind, on lumenlearning, and Medium. It has been applied to everything from work productivity to sports performance and the impact of anxiety on learning. But how did this research finding become a “law”? What did the original researchers do and what did they find? And how well has this been replicated?

The original study

Get ready to be shocked (pun intended). The Yerkes-Dodson law and very likely your own belief that your learning will be optimized if you’re a little stressed (but not too much), comes from… 12 Japanese dancing mice who were learning that walking into a black box would result in a shock, but walking into a white box would not.

The original study was a set of three experiments where the researchers manipulated things like how big of a shock the mice received and how easy it was to tell the difference between the white and black boxes. Even within the original study, they only found the classic U-shape in one of the experiments, concluding that the effect depends on the task difficulty. In addition, this set of experiments has a lot of methodological flaws that have been called out (3).

Ok, so the original study was on mice. That’s true for lots of things we know about learning. A lot of the original studies on reinforcement and punishment were conducted on rats or pigeons (4), but later replicated with humans (5). So, let’s talk about the replications of the Yerkes-Dodson “law” in other conditions.

This study was replicated with baby chicks (6) and kittens (7) and didn’t really replicate. There was no point in which the rate of learning slowed as the stress (shocks) got higher. Now, there have been some later studies looking at the relationship between stress and performance in humans, but very few find anything that looks like Yerkes-Dodson. In fact, far more studies find a clear trend in which more stress equals lower performance.

So, why is Yerkes-Dodson still so popular?

There are a few potential reasons for this.

1) It’s easy to find reputable people who you can cite talking about Yerkes-Dodson. It’s hard to put to rest a myth that is so darn prevalent. Admittedly, I taught this when I first started my teaching career because it was highlighted in the intro psych textbook I was teaching out of and I didn’t know any better!

Image by silviarita on Pixabay

2) It makes sense. All of my fellow procrastinators know all too well the feeling of a deadline approaching. As that stress builds a bit, so does our motivation to complete the task in front of us. And certainly many of have experienced the feeling of being paralyzed by having so much to do that we freeze. This all sounds really normal, right? So, this becomes something that would fall into the category of common sense. The problem is what people have argued based on this. The idea that maybe we should introduce stress into the workplace in order to get folks moving based on the data that we have simply doesn’t make sense.

3) It’s nearly impossible to prove wrong. Let’s talk about those studies where folks found the negative impact of stress on performance. Well, maybe they just didn’t have a condition with low enough stress to see the other side of the curve. Similarly, if you found no effect, well maybe you were just at the very top of the curve. This is called circular logic and renders for a really bad theory – one that is not falsifiable – one that we can’t really test because the results don’t definitely prove anything.

What should you do with this information?

I’m not arguing that this is a myth that needs busting necessarily, but with all new strategies, arguments, and policies, be skeptical. Do your homework and know that the strategy is based on solid evidence. In the case of Yerkes-Dodson, you’re on shaky ground. I don’t advise you to go out and try to stress your learners so that they perform a little better. There really isn’t justification for that… even if Yerkes-Dodson were accurate, you don’t know where they are on the curve with just, you know, life!

I take this as a really good lesson for both doing your homework before making big changes in your learning environment and also evaluating your own outcomes. Just because your psychology textbook said you should do it, doesn’t mean that it will always work the same way with your unique context, learners, and materials. You are the expert when it comes to your classroom.

For more information

If, like me, you found this totally fascinating, here are a couple of quick resources where you can read more details:

1) https://www.simplypsychology.org/what-is-the-yerkes-dodson-law.html

2) Corbett, M. (2015). From law to folklore: work stress and the Yerkes-Dodson Law. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(6), 741-752.

References:

(1) Yerkes, R.M., and Dodson, J.D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology of Psychology, 18(5), 459-482.

(2) Diamond D.M., et al. (2007). The Temporal Dynamics Model of Emotional Memory Processing: A Synthesis on the Neurobiological Basis of Stress-Induced Amnesia, Flashbulb and Traumatic Memories, and the Yerkes-Dodson Law. Neural Plasticity, 33. doi:10.1155/2007/60803.

(3) Corbett, M. (2015). From law to folklore: work stress and the Yerkes-Dodson Law. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(6), 741-752.

(4) Reynolds, G. S., Catania, A. C., & Skinner, B. F. (1963). Conditioned and unconditioned aggression in pigeons. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 6(1), 73.

(5) Berkowitz, L. (1983). Aversively stimulated aggression: Some parallels and differences in research with animals and humans. American Psychologist, 38(11), 1135..

(6) Cole, L. W. (1911). The relation of strength of stimulus to rate of learning in the chick. Journal of Animal Behavior, 1(2), 111.

(7) Dodson, J. D. (1915). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit-formation in the kitten. Journal of Animal Behavior, 5(4), 330.