Effective Learning Strategies depend on Prior Knowledge

by Cindy Nebel

(cover image by OlgaVolkovitskaia on Pixabay)

When it comes to knowledge, the rich really do get richer. When we take in new information, it gets linked to what we already know. So, if we have more prior knowledge in an area or we can understand new information in the context of what we already know, we are more likely to understand it and to retrieve it later on.

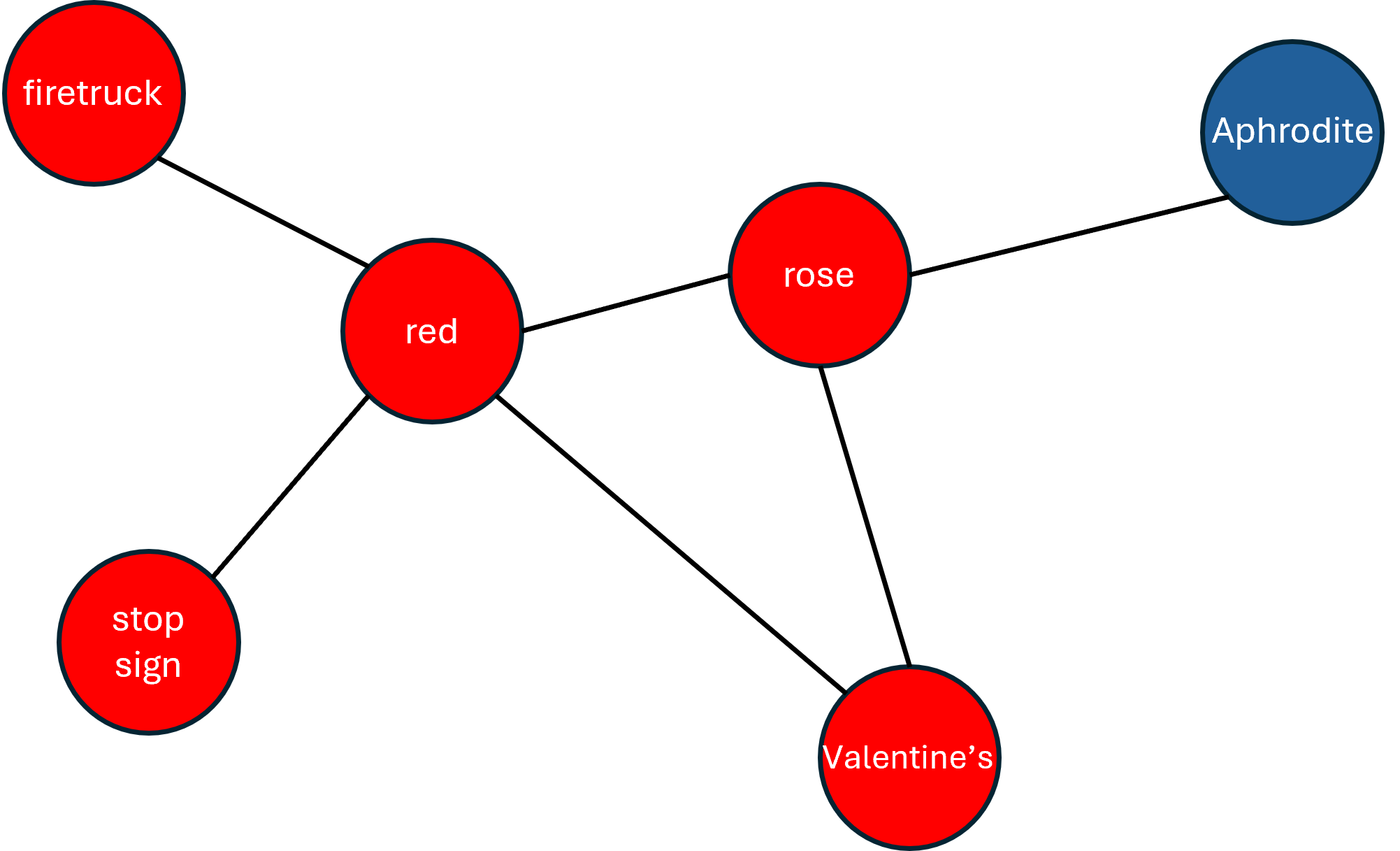

This is because knowledge is stored in something like a web. And whatever is connected to a concept becomes a way to access that knowledge later on. Take for example a simple concept - the color red. In many minds, red is connected to fire truck, stop sign, rose, and many other things. In turn, rose is connected to petal, flower, Valentine’s Day. Now let’s say I’m in class learning about the Roman goddess Aphrodite, who supposedly had roses spring up wherever she walked. My existing knowledge of the association between roses and Valentine’s Day will help me to understand and retrieve the fact that Aphrodite was known as the goddess of love.

Image created by author

This is a very simplistic example, of course, but demonstrates how our existing knowledge helps us to make sense of incoming information. It gets a bit more complicated than this when we consider how we organize our prior knowledge.

Image created from methods of cited source

In one now famous study (in some circles), students were divided into groups based on their reading comprehension skills and their knowledge of baseball (1). After reading a passage about baseball, there were two main effects. Students with higher reading comprehension skills performed a bit better than students with low reading comprehension skills, but the much larger effect was that of prior knowledge. What’s going on here?

Image created from results in cited source

*Quick aside: Sometimes this study is used to argue that reading comprehension skills don’t matter. That’s not our interpretation. Rather, this study was set up very carefully to show the power of prior knowledge in particular.

Part of this effect is due to chunking. For folks who know a lot about baseball, they likely can process a description of a double play as one thing. That makes sense to them. For me, a double play would involve a series of distinct events that I process individually, because I know very little about baseball. (What is a double play anyway?) Another classic study looks at how chess masters process chess boards (2). Where I see many distinct pieces on the board (a horse, a castle…), they see something like, “ah, classic… that’s the queen’s gambit”.

Novices, beginners, folks with little prior knowledge literally think about concepts differently than those with prior knowledge. It’s not just that they can build on those connections, but the thinking is qualitatively different. Novices need more working memory to process all those distinct chess pieces, but experts need more complex tasks to feel challenged and reach the desirable difficulty needed for effective learning.

Therefore the strategies that work best for novices differ from those that work best for experts. Novices tend to learn best with guidance - with direct instruction of some kind. They need structure because their working memories are taken up with individual pieces of new information. Experts, on the other hand, learn best when they are left to their own devices and engage in problem-solving or inquiry. They can handle the added challenge, which in turn leads to better learning.

This general idea that what works best for novices is the opposite of what works best for experts is called the expertise reversal effect and explains why scaffolded instruction and gradual release is often very successful in the classroom (3). As students go from novice to expert in an area they will learn most effectively if they go from direct instruction to maybe worked examples or instructor-supported practice to independent, problem-based, or inquiry-based approaches.

Image created by author

This applies to student self-directed learning as well. In medical education for example, students should start by trying to acquire factual information through reading, watching lectures, or even through flashcards (all with appropriate note-taking or other processing). Once the basics have been acquired, though, students should move to more complex learning such as answering questions about clinical cases where sometimes there isn’t one correct answer.

This means that despite many different arguments about how we should assess our learners to determine the most effective strategy for them to learn, often the most important assessment should simply be how much they already know.

References:

(1) Recht, D. R., & Leslie, L. (1988). Effect of prior knowledge on good and poor readers' memory of text. Journal of educational psychology, 80(1), 16.

(2) Gobet, F., & Simon, H. A. (1998). Expert chess memory: Revisiting the chunking hypothesis. Memory, 6(3), 225-255.

(3) Chen, O., Kalyuga, S., & Sweller, J. (2017). The expertise reversal effect is a variant of the more general element interactivity effect. Educational Psychology Review, 29, 393-405.