Spacing Retrieval is More Important than Extra Retrieval

by Cindy Nebel

A few weeks ago, Megan wrote this blog about the benefits of spaced retrieval practice on long-term learning and transfer of course material. And I have to admit, it’s a pretty cool study (1)! But we should never change our practices based on one study alone. Researchers know this and that’s why they replicate experiments.

And so the researchers have again shown the benefits of spaced retrieval practice, but this set up was a little different (2). What you are about to see is that it isn’t about how much you study, but about how you study. Quality wins over quantity and we all get to save a little bit of time… making this great news for busy students (and teachers) everywhere!

The Experiment

As with the earlier study that Megan reviewed, the researchers studied pre-engineering students who were enrolled in a precalculus course and followed them into their calculus course the following semester. In the precalculus class, students learned about lots of different topics, took quizzes, exams, and a cumulative final.

This experiment might look a bit different than what you’re used to seeing. Participants were not split into groups. Rather, the researchers manipulated the way different topics were quizzed over the course of the semester. They were interested in how much you should quiz something, whether you should space out the quizzing, and which mattered more for long-term retention the following semester.

The topics were split into four conditions

Baseline: This is how most math classes are set up. These topics were covered in class and then there were three quiz questions that asked about that specific topic on the weekly quiz.

Extra Spacing: In this condition the three quiz questions were spread out across four different weekly quizzes.

Extra Quizzing: In this condition, the weekly quiz had six questions instead of just three, so they received more practice.

Both: In this condition, they spread out all six quiz questions across four different weekly quizzes.

Here’s a picture that shows this, adapted from one provided by the researchers:

Image adapted from cited source

Throughout the first eight weeks of class, topics were assigned to one of these four conditions. This means that each student received weekly quizzes that contained questions covering the current week but also previous weeks and which questions they received depended on the condition for each topic. This is called a within-subjects design. If I were a participant, you would be able to compare how I did on topics in the baseline condition with the other three conditions because I received all four. So we can look across participants and see if they all performed similarly across these different types of quizzing.

The Results

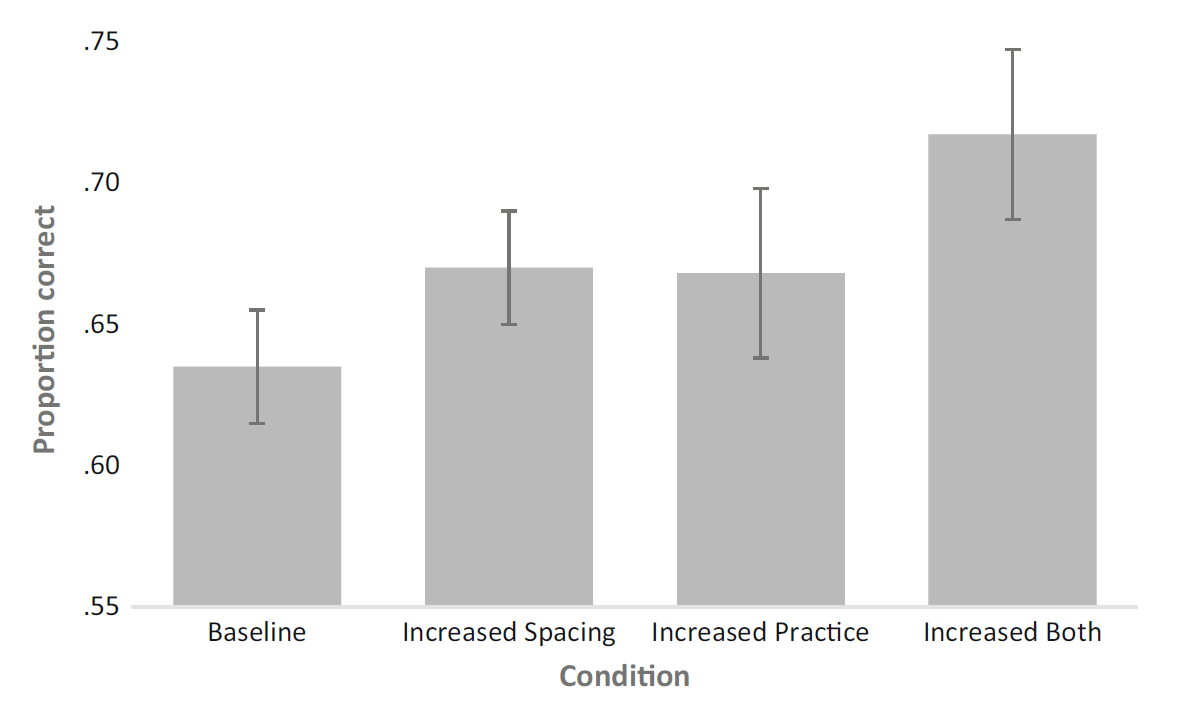

Y’all, this is cool. The researchers looked at the results in a couple of different ways. When looking at the final exam at the end of the semester here is what they found:

Image from cited source

Turns out that spacing and retrieval practice were both equally good and adding them together provided an extra punch. This isn’t entirely surprising. There is plenty of research showing the benefits of spacing and retrieval practice on learning.

But they also looked at retention. Arguably, both researchers and students should care much more about how much was retained between semesters. Students who remembered more will be much better prepared in Calculus and likely will perform better in that class as well. (Successful study habits are a bit like compounding interest!)

When we look at the forgetting that took place across semesters, researchers found that the positive effects of spacing stayed the same - that is, having spaced quiz items in the preceding semester still led to better performance on the pre-test four weeks later. But, interestingly, the benefits of increased quizzing disappeared. Students were no better having been quizzed with three items vs. six items on that topic when looking at performance four weeks later.

So what?

Image from Pixabay

Let me phrase those results a different way. Taking the same amount of time and energy that it took to write the normal quiz for a class and just distributing those questions across a couple different quizzes was more beneficial than writing and answering (and grading?) additional quiz questions.

Educators: Quiz your students. Absolutely you should incorporate retrieval practice. Just space it out over time instead of providing blocked weekly quizzes just over that week’s content. But congratulations! You don’t have to do the extra work of writing and grading more quiz questions to get this benefit!

Students: Quiz yourselves and when you do, make sure you’re reviewing old material. Build in frequent study sessions, but you don’t have to double the time you’re spending studying to get great benefits, as long as you’re doing what you should be doing throughout (spaced retrieval).

Caveats

I started this blog by saying you shouldn’t change your habits on the basis of one study. And then I told you to change your habits on the basis of this study…

This study in housed in a large body of research, making me feel pretty confident about those tips above. That said, there are some things to consider here. This research was done with precalculus engineering students at a university. They’re probably not representative of everyone. Even further, in order to analyze the data, the researchers could only look at students who actually took all of the quizzes (about half the class). Their behavior may have been different (i.e. they may have studied a lot more outside of class), which could influence these results.

Another important result in this study is that increased spacing reduced quiz performance. Even though students remembered more of the material long-term, their initial performance wasn’t great. This is so important. Students are not going to like this. It’s harder than taking a weekly quiz over what they just learned. It’s also important that educators not “punish” students for this reduced initial performance. If we want to encourage students to engage in a behavior at home that is going to lower their grades in class… that is arguably unethical as grades (perhaps unfortunately) determine much of their future success. Educators need to express this to students. They need to understand why they are doing something different and harder than they’ve done before and they need to be provided with the psychological safety to fail early for later gains. In other words, quizzes should be low or no stakes in order to reduce the anxiety involved with what will inevitably be lower initial marks.

Bottom Line

Retrieve old stuff.

No, really. The bottom line here is that you should be utilizing retrieval and you should space it out, but you don’t need to worry about doing so over and over and over again necessarily (although a few times to get that spacing in is necessary). And it’s going to be hard, but that is going to lead to better retention and therefore better performance on the final and in the next class. #worthit

References:

(1) Hopkins, R. F., Lyle, K. B., Hieb, J. L., & Ralston, P. A. S. (2016). Spaced retrieval practice increases college students’ short- and long-term retention of mathematics knowledge. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 853-873.

(2) Lyle, K. B., Bego, C. R., Hopkins, R. F., Hieb, J. L., & Ralston, P. A. (2020). How the amount and spacing of retrieval practice affect the short-and long-term retention of mathematics knowledge. Educational Psychology Review, 32(1), 277-295.