Optimizing Your Learning Schedule

By Carolina Kuepper-Tetzel

One of the most effective learning strategies is spaced practice – the distribution of study time across multiple smaller study sessions. This learning strategy dates back to Hermann Ebbinghaus in 1885 who conducted the first systematic investigations of spaced practice with himself as a participant; studying random syllables. Most research after that has usually used a simplified design to investigate spaced practice: using two study sessions only (initial study session + review session) and varying the interval between them. Although this approach makes sense, e.g. for testing theories of the spaced practice effect and feasibility to run experiments in the laboratory, it is usually not a realistic representation of real-world learning. In authentic educational settings, students and teachers will revisit previously-taught material more often than just once. Thus, the question is: How should your learning schedule look like when you plan reviewing older material in more than one review session?

Image from Pixabay

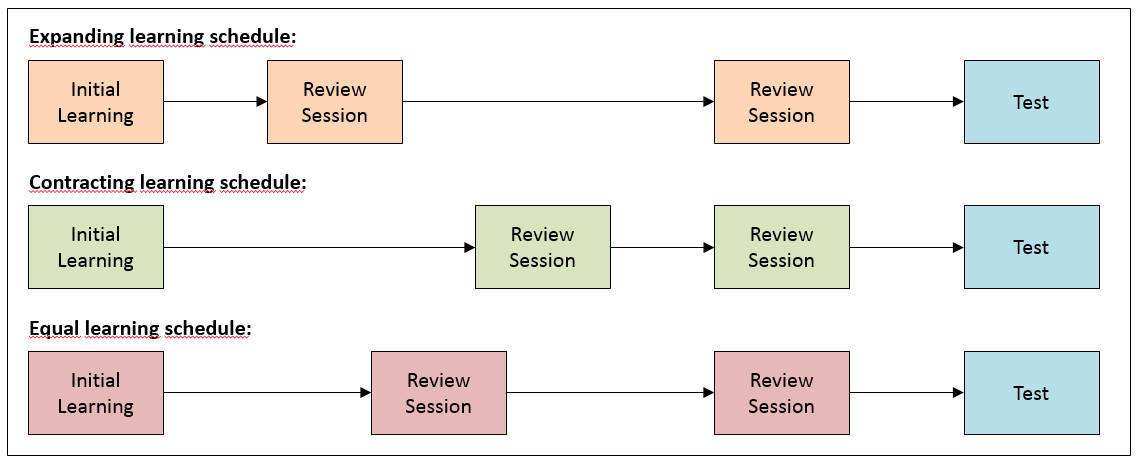

If we think of learning schedules in a systematic way, there are, in principle, three distinct learning schedules that one can adopt. The difference between them is whether the intervals between study sessions increase, decrease, or are kept the same (see figure below). When the intervals increase between two sessions over time, we refer to it as an expanding learning schedule; when the intervals decrease between sessions over time, we call it a contracting learning schedule; and when the intervals are of the same lengths throughout, it’s an equal learning schedule.

Several studies have pitched the different learning schedules against each other to test which one is more beneficial for knowledge maintenance. Taken these different findings together, research suggests that expanding and equal learning schedules often lead to similar test performance and contracting learning schedules are usually found to be inferior compared to the other two.

Interestingly, the time between the last review session and the final test seems to affect the optimal learning schedule. In a study by Kuepper-Tetzel, Kapler, and Wiseheart (1) participants studied vocabulary using an expanding, contracting, or equal learning schedule. Afterwards they were tested on the vocabulary on a final test either immediately, 1 day, 7 days, or 35 days later. What they found is that for the immediate test it did not make a difference which learning schedule was used. For the tests given 1 day or 7 days later, a contracting learning schedule outperformed the two others (a finding at odds with most previous research). However, on the test given about one month later, expanding and equal learning schedules led to better results than the contracting learning schedule. Thus, it seems that if the goal is to maintain previously-taught material for a long period of time, we should either adopt an expanding or equal learning schedule. For short-term successes contracting learning schedules can show benefits.

However, it needs to be pointed out that previous studies have often failed to show any benefit of a contracting learning schedule. One feature of the just presented study was that participants learned the material to perfection during the initial learning session. A very recent study by Toppino, Phelan, and Gerbier (2) revealed that indeed the level of initial practice plays an important role in determining which learning schedule is most beneficial: They showed that when initial level of practice was high (participants took practice tests with feedback), then it did not matter which learning schedule was used. However, when initial level of practice was low (participants reread the material), an expanding learning schedule outperformed all other schedules on a final test 2 weeks later.

Image from Pixabay

Where does this leave us? Given that education should emphasize long-term retention of knowledge instead of shorter-term gains, research would encourage using an expanding or equal learning schedule. Further, after the first exposure to new material, e.g., when the teacher introduces a new topic in class, students have usually not obtained a high level of understanding of it, thus, an expanding learning schedule seems to be the best choice here.

But there is more: From a practicability point of view, the implementation of an expanding learning schedule seems more feasible than trying to stick with equal intervals between study sessions. The key of implementing spaced practice successfully is to make sure to review older material before it is forgotten. Thus, leaving too much time between study sessions can lead to too much forgetting, which would be detrimental for learning as a whole. An expanding learning schedule is an effective way to counteract this by gradually increasing intervals between review sessions.

To make your review sessions even more effective, do not simply review older material by rereading it, but rather by taking practice tests during your review sessions. If you do this with an expanding learning schedule, you are using an expanding retrieval schedule (we got a name for almost everything).

References:

(1) Kuepper-Tetzel, C. E., Kapler, I. V., & Wiseheart, M. (2014). Contracting, equal, and expanding learning schedules: The optimal distribution of learning sessions depends on retention interval. Memory & Cognition, 42, 729-741.

(2) Toppino, T. C., Phelan, H.-A., & Gerbier, E. (forthcoming). Level of initial training moderates the effects of distributing practice over multiple days with expanding, contracting, and uniform schedules: Evidence for study-phase retrieval. Memory & Cognition.