GUEST POST: Strategies for Effective Learning - A Whole School Approach

By Dawn Cox

Image from Twitter

Dawn Cox is a secondary teacher in Essex, England. She blogs here and can be found on Twitter @MissDCox.

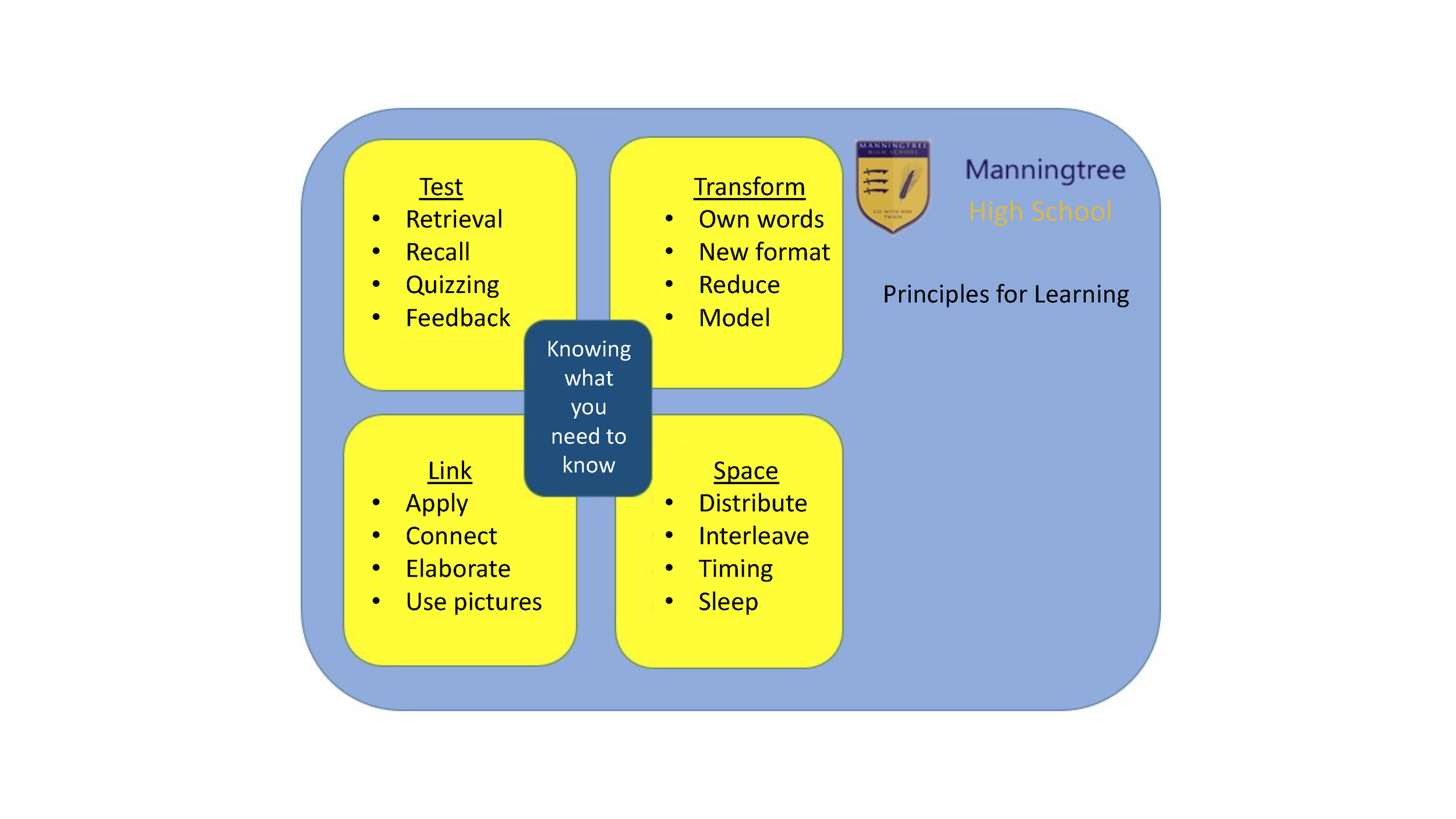

My school has started implementing a whole school approach to learning, based on what cognitive science suggests might be successful strategies. I’ve been working with colleagues on a set of ‘Principles for Learning’ that give teachers and students some suggested methods to use from ‘day 1’ of learning something. These methods are all based on evidence from cognitive psychology, although we had already decided to frame them under four areas that are slightly different than the six strategies.

We decided to frame the strategies in terms of 4 principles: Test, Transform, Link, and Space. Relating these principles to cognitive psychology, “Test” maps onto retrieval practice, while “Space” maps onto spaced practice and interleaving. “Link” includes techniques based on dual coding and elaboration, whereas “Transform” could be thought of as encouraging transfer.

We also decided that an additional point (“knowing what you need to know”, superimposed in the center of the diagram above) was crucial, because if you don’t know what it is that you already know and what you need to know, you don’t have a concrete starting point. You may learn things that aren’t needed or confuse yourself with additional detail. My own students like the fact that I give them the specification outline and all the keywords they need to know for their GCSEs (American readers – see this post for an explanation of these important exams in the British education system); this way, they know what they’ve got to learn.

We elaborated each of the 4 principles with the kinds of things that teachers could do to use them in lessons, as well as the kinds of things students could do to use them during private study. It was very important for us to keep it as simple as possible. The principles are equally for teachers as they are for students (in our case, kids aged 11-16), so they both need to easily understand and apply them.

Image created by Dawn Cox

We deliberately haven’t mentioned “revision” (for American readers: this is a British term that refers to the intense study period prior to high-stakes exams) anywhere in the model. The idea of revision, as it exists in most people’s minds, is something that is done far too late. Embedding these principles needs to start from lesson 1 and continue infinitely.

We also wanted to ensure that the principles were universally applicable. They are easily embedded in some subjects such as maths and history; however, we could see that there was limited application for some of the principles in subjects like Art. Having said that, colleagues in Art could see how they could adapt the strategies in key stage 3 (age 11-13) in a way that would go on to benefit GCSE (age 13-16) students; subjects such as PE and Drama now have much more theory that these could easily apply the principles.

Subject departments have identified one particular aspect they’d like to try out with their students. They have been supported by 15-minute forum CPD sessions on ideas for how to use each strategy. Each teacher has also been given an A3 version of the diagram above for their classroom.

So far the students have had:

A survey on learning and how they think it ‘works’, so we can see any common misconceptions and examples of how the principles are already being used.

An assembly on the principles outlined above, and a physical demo to try and show the difference between spacing and cramming. This involved a set of netted hoops spaced equally across the hall. Two willing volunteers were given balls to get into the nets.

Image from Pixabay.com

One started when the timer began, taking a measured and consistent pace. He confidently managed to ‘hoop’ all the balls because he could be accurate due to his slow, steady, spaced pace. The other participant was busy checking his phone when the timer began. He lacked focus. He suddenly realised that he had a task to do and with little time left had to run fast to have a chance of getting any hoops. In his haste, he was less accurate and had to sprint to get past all the hoops. This was designed by the Deputy Head to try to illustrate that leaving it to the last minute may get some results but they won’t be as ‘good’ as those that use their time fully, spreading practice across the time available.

A tutor session with centralized resources for tutors to use on ‘Testing’.

Still to happen:

We will regularly work with teachers on using their strategy, e.g. a 15-minute forum on how I use Google Forms for quizzes

Teachers will use and identify the ideas more and more (using the language of these strategies), including when they set ‘revision’ for homework, and use these strategies specifically instead of just saying ‘revise’

We will reissue the survey to see any changes in student understanding of what helps them to learn

We will put links to relevant resources (e.g., posters) on our school website

How will we know that these strategies have made a difference?

We won’t know if they’ve made a real difference in learning without a controlled experiment, which we are not in a position to run at the school. We can ask staff, students, and parents if they’ve used the strategies and whether they feel they help or not (although we have to be careful because sometimes the strategies that “feel” the best are actually the least effective). We can see what happens when we tell students to do something like ‘learn these spellings’ – do they respond with one of the strategies, and therefore pick an efficient method? However overall, we won’t be able to ‘measure’ impact; instead, we rely on the existing well-controlled research demonstrating that these strategies are effective, and based on this research, we believe that knowledge of these strategies can benefit teachers and students enough that it’s worth the effort to share and promote their use.

A version of this blog post originally appeared on Dawn Cox’s blog, missdcoxblog: My views on Teaching and & Education.