What's Transfer, and Why is it so Hard to Achieve? (Part 1)

By: Cindy Wooldridge & Yana Weinstein

One of the critiques that we receive as cognitive psychologists is that testing encourages rote memorization, which is not the goal of most educators. We understand the critique; our goal is rarely to simply transmit raw facts to our students. Instead, we want our students to be able to use their knowledge to solve problems in the “real world”.

This application of knowledge and skills is called transfer by cognitive psychologists, and it is often considered a primary goal of education; and yet, it is extremely tricky to achieve. However, to the extent that it can be achieved at all, testing can help with this goal, too.

A helpful distinction can be made between near and far transfer. Transfer can be conceptualized as a continuum. If you are transferring information to something very similar, such as a question that asks about the same material but in a new and different way, we refer to that as near transfer. If instead we ask students to apply their information to solve a novel problem or explain a real-world scenario, that would be considered far transfer. Again, these are on a continuum, from very near to very far.

In this post, we will focus just on near transfer, and discuss two sets of studies: one in which near transfer was achieved, and one in which it wasn’t.

When Transfer Was Obtained:

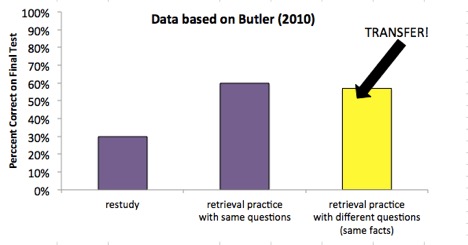

Butler (1) conducted a series of experiments to determine when and if retrieval practice (2) could promote transfer of knowledge. In all experiments, college students read passages and then were told to study half of the passages and took quizzes with feedback on the others. After one week, participants took a test on all of the passages.

In the first experiment – which did not look for transfer at all – the initial quizzes and final test included the same questions. In the second and third experiments – which looked for near transfer – the final test included questions that were rephrased from the initial quiz, but targeted identical facts/concepts, as in the following example:

Original Quiz Question:

Bats are one of the most prevalent orders of mammals. Approximately how many bat species are there in the world?

Rephrased Test Question:

Chiroptera is the name of the order that contains all bat species. What is the approximate number of bat species that exist?

These rephrased questions represent very “near” transfer because the questions are targeting the same information but in a slightly different way.

The results from these three experiments demonstrate the typical testing effect: participants performed on average 27% higher on previously quizzed items than they did on re-studied passages across the three experiments.

Graph showing near transfer after quizzing, based on data from (1).

When Transfer Wasn’t Obtained:

In a series of two experiments, together with my colleagues I (Cindy) (3) sought to find transfer using a quiz bank that accompanied a textbook. The design of these studies was rather complex, but here we are going to pull out one key set of conditions: highlighting, retrieval practice on same questions as the final test, and retrieval practice on different questions – which at least superficially sounds like the study you just read about, right? Well, read on.

In both experiments, participants read a textbook chapter and then were either given time to study and highlight the chapter, or took quizzes. The quizzes included either identical questions to the final test, or questions on related material that were taken from the same 1-2 paragraph section of the textbook chapter:

Factual Quiz Question:

Estimates of evolutionary relatedness based on the ‘molecular clock’ are supported by what?

Related Factual Quiz Question:

The longer two species have been evolving on their own, the greater the number of ____ that accumulates between them.

The results demonstrated the typical testing effect such that performance on identical questions was 20% higher than the highlight condition. However, there was no transfer: performance on the facts that were related to the quizzes facts was no better than performance after highlighting.

Graph showing lack of near transfer after quizzing, based on data from (3).

In the second experiment, the initial quizzes were marked for correct or incorrect answers and participants were instructed to go back and review the chapter to determine why they missed items (as they might be expected to do in a classroom environment). After this review, there was no significant difference between highlighting and the quizzing condition on the different facts, showing no transfer from the quizzed information to the related test questions.

Importantly, we started by surveying instructors about these materials, most of whom said that we should get big benefits on the final test for these related questions and that they quiz their students expecting transfer to related questions in their classrooms!

When do we typically find transfer?

A key difference between the studies above is that in Butler’s study, the exact information on which participants were quizzed could be used in the new situation (i.e., to answer a differently worded question). In our study, we were hoping for a boost of quizzing on related information, and the exact information that students practiced might not have been useful in this particular transfer situation.

What does this tell us about teaching for transfer?

There are a few lessons to take away from this information. In order for transfer to be successful, students need to be aware of the transfer situation, be able to retrieve the prior knowledge, and use it appropriately (4).

Transfer is difficult to achieve, but is a main goal for educators. Research demonstrating transfer typically comes from very controlled laboratory studies, but this does not mean that it is not possible in the classroom. It means that we, as educators, must be cautious when trying to achieve transfer. What is intuitive to us does not always match up with what works, so we must critically evaluate the research to determine how we can best achieve our goals. In this particular case, a technique used by many teachers – quizzing some information in the hope that it will “trigger” other related information at test – didn’t work (3); but quizzing specific information in one way did lead to the ability to produce that same information in response different question (1).

Next week, we will talk about far transfer!

If you liked this post, you may be interested in some of our other research summaries:

How To Study A Textbook: A Researcher’s Perspective

I'm A Teacher Who Loves Quizzing; But Does Quiz Format Matter?

I'm A Teacher Who Loves Quizzing: But Where Should The Quiz Questions Go?

Retrieval Strength Vs. Storage Strength

References:

(1) Butler, A. (2010). Repeated testing produces superior transfer of learning relative to repeated studying. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition, 36, 1118-1133.

(2) Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). The power of testing memory: Basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1, 181-210.

(3) Wooldridge, C., Bugg, J., McDaniel, M., & Liu, Y. (2014). The testing effect with authentic educational materials: A cautionary note. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 3, 214-221.

(4) Barnett, S. M., & Ceci, S. J. (2002). When and where do we apply what we learn? A taxonomy for far transfer. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 612-637.