What to do About Course Evaluations

By Cindy Wooldridge

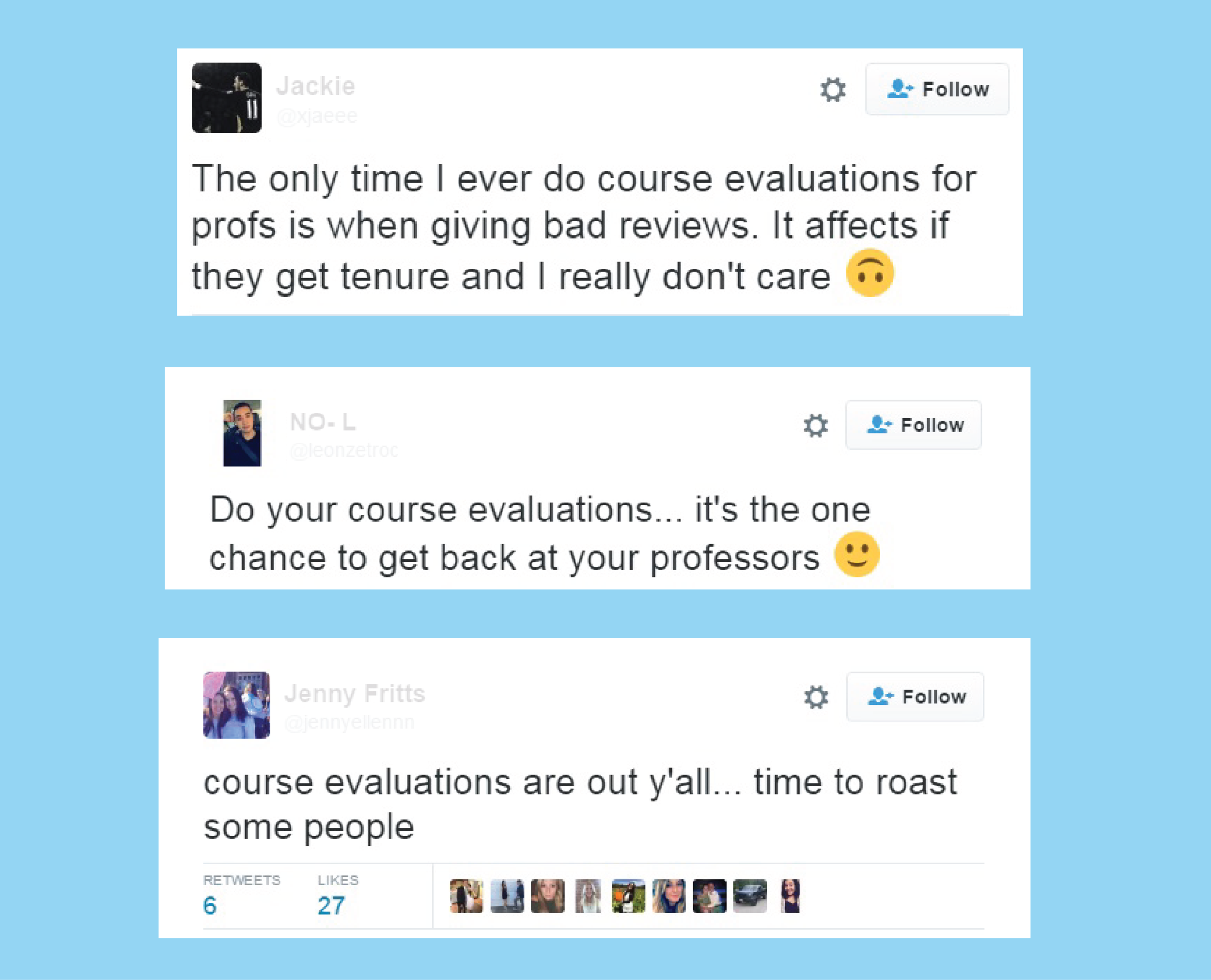

As an instructor in higher education, this time of year brings a bit of trepidation. As a tenure-track professor at a teaching university, this time of year can make or break my future. Reading the tweets, shown in this post, made me realize that course evaluations may mean something considerably different for students than administrators, colleagues, or I realize. Given that it is evaluation time at many universities, I thought it might be worthwhile to take a moment to talk about the value and utility of course evaluations as well as ways in which professors might be able to improve their evaluations.

What are evaluations good for?

Earlier this year, Uttl et al (1) published a large meta-analysis showing that, in short, there was no relationship between instructor evaluations and student learning. The authors demonstrated that previous reports showing such a relationship were flawed and should probably not be considered. This is likely due to small sample sizes and the fact that significant findings are much more likely to be published than non-significant findings.

This article follows others that carry serious concerns. For example, women tend to receive lower course evaluations than men, regardless of actual teaching effectiveness (2). Evaluations tend to have low response rates and averaging the results across courses and students ignores important variables that might affect evaluations, such as the type of course or the variability in student responses (3). If my teaching is not effective for a certain population, say, first-generation college students, that would be much more important that knowing my average score was 4.5/5 on a given item.

Image from Pixabay.com

Therefore, according to the widely spread findings above, it appears that course evaluations (as currently administered and interpreted) are just not very valid measures and probably shouldn’t be used to make big decisions about whether or not to hire faculty or grant tenure.

So why do we keep them around?

Hopefully the readers of this blog will not be surprised to find out that widely spread findings rarely tell the whole story. Such is the case for course evaluations. While the above findings are real and their criticisms should be considered, most have their own limitations as well.

For example, the finding that there is a gender bias in evaluations comes primarily from laboratory research, whereas in large-scale studies of actual evaluations, gender discrepancies are rarely found (4). And it turns out that student evaluations are strongly correlated with peer evaluations by other instructors (5). I strongly recommend that you peruse this article in defense of course evaluations for a review of the literature and a rebuttal of many of the common misconceptions related to evaluations. Much of what follows in this post was found within that article.

Here’s the biggest kicker, though: student opinions do matter… don’t they? When we’re talking about teaching, surely the students should have some say in whether or not the instructor was effective. The easiest way to hear what they have to say is simply to ask them, which is why course evaluations are likely not going anywhere anytime soon. The evaluations themselves can likely be improved at certain institutions. A single question that asks, “How effective was this instructor?” is likely not as telling as items that relate to different aspects of teaching (although at my institution, these items are all strongly correlated with the overall assessment question).

So, in short, we keep course evaluations around because it’s important to include students’ opinions in discussions of teaching effectiveness… but their opinions should not be the only ones that matter. In order to get a global view of teaching effectiveness, student course evaluations should only make up part of the picture. Institutions might also consider peer or self-evaluations, changes and improvements over time, or even things like professional development through teaching workshops and quality of materials used in class… all of which have their own shortcomings.

What can I do about it?

The good news is that course evaluations can improve over time. Simply provide students with baked goods, give them lots of extra credit, and allow them to make up any assignment for full points. All joking aside, personality characteristics and even “hard” vs. “easy” classes do not seem to be great predictors of course evaluations. But here are some things that you can do to improve your evaluations:

1) Be more organized. Students rate instructors who are more organized higher than those who are less organized. You might consider having a clear agenda for the semester as well as for individual class periods. Also, try to make your expectations for students clear. Students are able to pick up on this characteristic on day 1, when they receive your syllabus. If it is well-organized, it might improve your evaluations.

2) Be enthusiastic. Students rate instructors higher when they appear passionate about the subject that they are teaching and are energetic in the classroom. Here we might be talking about general presentation skills such as eye contact, volume, and movement around the room. If you appear to care about the subject, students will respond positively. If you appear bored and tired, students will find your teaching boring and tiring.

3) Be confident. Students rate instructors higher when they display positive self-esteem and confidence in their performance. Appearing more confident may again take into consideration presentation skills such as not hiding behind a podium, explaining the purpose behind assignments and activities, and being willing to answer questions even if the answer is something like, “based on my knowledge I believe [this], but that is speculation and I will find a better answer for you and address it next class”. If spoken with confidence, a lack of knowledge is not necessarily a bad thing.

Image from Pixabay.com

Bottom line

Course evaluations are probably not going anywhere anytime soon. You can use the above tips to try to improve your evaluations, but know that these tips are things that should be done starting at the beginning of the semester, as first impressions are predictive of later evaluation ratings (6). Instead of sweating over this semester’s ratings, perhaps you can start a dialogue at your institution about broadening the way in which teaching is assessed in order to reduce the power of a single score.

References:

(1) Uttl, B., White, C. A., & Gonzalez, D. W. (2016). Meta-analysis of faculty's teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation, DOI: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.08.007.

(2) Boring, A., Ottoboni, K., & Stark, P. B. (2016). Student evaluations of teaching (mostly) do not measure teaching effectiveness. ScienceOpen, DOI: 10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR-EDU.AETBZC.v1.

(3) Stark, P. B., & Frieshtat, R. (2014). An evaluation of course evaluations. ScienceOpen, DOI: 10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR-EDU.AOFRQA.v1

(4) Li, D., Benton, S. L., & Ryalls, K. (in press). IDEA Research Report #10: Is there gender bias in IDEA Student Ratings of Instruction? Manhattan, KS: The IDEA Center.

(5) Feldman, K. A. (1989a). Instructional effectiveness of college teachers as judged by teachers themselves, current and former students, colleagues, administrators and external (neutral) observers. Research in Higher Education, 30, 137-194.

(6) Ambady, N., & Rosenthal, R., (1993). Half a minute: Predicting teacher evaluations from thin slices of nonverbal behavior and physical attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 431-441.