Learning “Useless” Things in School is (Usually) NOT Useless

By Cindy Nebel

Image by Bernard Lamailloux from Flickr (CC BY 2.0). Text added by Megan Sumeracki via Kapwing.

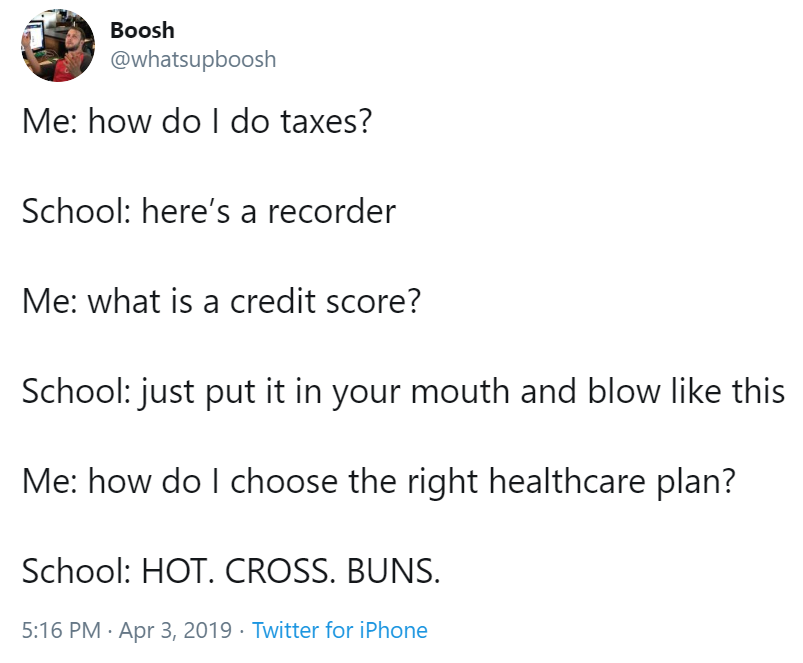

I’ve seen a steady stream of memes like this one on my Facebook news feed. Understandably, students are frustrated when they enter the “real world” and feel as though they weren’t adequately prepared for some of the practical life skills they needed and parents are equally frustrated putting in their precious free time helping with homework on topics they’ve never used. I’m not here to argue whether we should provide lessons on life skills, but what I want to talk about today is the negative message that a lot of what students are learning in school is “useless”.

Most of the information that students and parents consider “useless” is likely knowledge without clear applications. How will students use algebraic expressions, structures of cell bodies, knowledge of fish species, or even *gasp* how auditory perception works (one of my favorite units to teach in introductory psychology courses)? In order to get to the heart of why this information might matter, we first need to talk about how knowledge is acquired and organized.

Image from Pixabay

We store knowledge in webs of associated information (1). When new information comes in, it gets embedded into the existing web, making connections with everything that is associated with it. So, if you’re trying to understand how something works, you activate the knowledge you have about that thing and the more knowledge you have, the more easily you understand it (2). And what’s really cool about this is that you don’t have to be able to recall it for this to work. So that means that even though I might not remember what I learned in the third grade during that awesome unit on fish, I could more easily appreciate and understand the exhibits at the new aquarium in St. Louis. I could understand and elaborate on what we saw in the exhibits and explain things to my 3-year-old son. Weeks later, I probably remember those exhibits better than I would have if they had been isolated bits of information with no existing knowledge.

The same is true for other seemingly useless bits of information. The practice you received using mathematical formulas in primary school likely makes you faster at solving problems that involve mathematics in “real life”. You are also likely better able to understand complex situations that involve math (e.g. political arguments regarding economics). While you may not whistle a tune on a recorder as an adult, those musical lessons helped you to be able to pick up a different musical instrument, enjoy a complex piece of music, or just appreciate the fact that, even if you don’t like the music, Tool is made up of extremely talented musicians.

Image from Twitter

The challenge facing teachers is to prepare a diverse set of students for later situations that are not only varied, but likely different from ones we can even imagine in our current time. As technology rapidly changes our world, our instructors are set with the task of attempting to make students ready for whatever that future world will throw at them. I would argue that teaching broad knowledge is the best way to do this. Those 8-year-olds could have any number of future professions and future situations. One of them might even take their kid to an aquarium as an adult. Teaching broad knowledge in the only way to prepare students for the broad world they are going to encounter.

While you may be frustrated that your child is in another “useless” unit, I would urge you not to let that feeling get passed to your child. In addition to the possible utility of the information, there is an abundance of research showing that students’ beliefs about the material they are learning is key to their ability to learn it. Showing excitement and building self-efficacy is a much better strategy than complaining about curriculum design or teachers’ instruction (3).

And if, by some chance, that lesson in school really has no use for the student’s future life, there’s another important lesson happening. It’s also possible that one day in the future, that student may need to sit through a truly pointless meeting, one that does not affect them in any way. Wouldn’t it be great for them to have some practice appreciating the information set before them, trying to make it relevant to their own lives, or simply appearing engaged? Practice makes perfect, after all.

For a commentary on how prior knowledge helps students with reading comprehension, learning, and problem-solving, check out this awesome piece by Daniel Willingham.

References:

(1) Chi, M & Koeske, R. D. (1983). Network representation of child’s dinosaur knowledge. Developmental Psychology, 19(1), 29-39.

(2) Recht, D. R., & Leslie, L. (1988). Effect of prior knowledge on good and poor readers' memory of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 16.

(3) Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological review, 84(2), 191.