How to Study a Textbook: A Researcher’s Perspective

By: Yana Weinstein

One thing that has always bothered me about the advice that students should practice retrieval is the lack of specific instructions regarding how they should go about actually doing it. It’s all well and good for us to tell our students they ought to do something – but unless the resources are there and the instructions are clear, only the most motivated and resourceful will put the advice into practice.

Imagine your daughter is studying for an exam. Having read our previous blog posts, you give your daughter the well-meaning advice: test yourself! Best-case scenario: she has plenty of practice questions similar to those she should expect to find on the actual exam. In this situation, my concerns are unwarranted and your child can proceed to the next step: practicing retrieval with those well-suited practice questions!

More often than not, however, such practice questions are conspicuously absent. Maybe there’s a multiple-choice quiz bank that goes with the textbook, but the teacher told her it wasn’t very good. What should your daughter do? Should she just re-read the textbook, or can she benefit from the testing effect by generating and answering her own questions on the material?

I decided it was important to examine what happened in this situation (1). To do this, I had undergraduate students at Washington University in St. Louis study four different passages on obscure trivia adapted from Wikipedia (in case you’re wondering, they were Salvador Dalí, the KGB, Venice, and the Taj Mahal).

The first passage was used for practice so students could get used to the format. For the remaining three passages, after reading the passage once, students then did one of the following activities with it: they either re-read the passage, answered some comprehension questions provided by the experimenter, or created their own questions and then wrote down their answers. Time was intentionally uncontrolled, so that students would take as along as they needed for each of these strategies.

After engaging in one of the strategies (re-reading the passage, answering questions, or generating and answering questions), students made a prediction of how much they would remember on a later tests. Then, a week later, students came back and took a short-answer test on the readings.

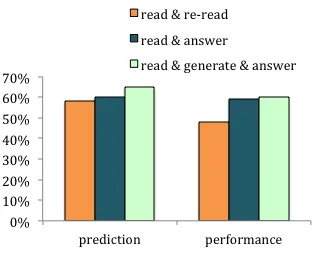

Data from Weinstein, McDermott, & Roediger (2010)

The left panel of the figure shows the predictions students made immediately after studying. Students thought they’d do best after generating and answering their own questions; meanwhile, they did not think that answering questions proffered any advantage over simply re-reading. In reality, both generating and answering and also simply answering the experimenter-provided questions led to a similar memory advantage compared to re-reading. But here’s an important caveat: remember how we didn’t control for time? Generating and answering questions took a lot longer.

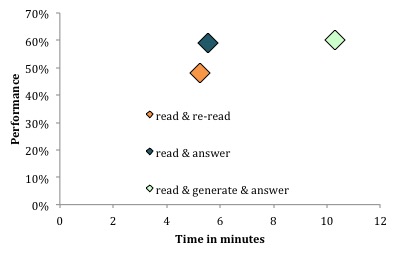

Although we didn’t plot the data this way in our paper, an interesting way to think about them is in terms of a time vs. performance gains trade-off:

As you can see, reading and answering questions gives a nice boost in performance with hardly any additional time – so if there are quiz questions your daughter can use to practice retrieval, it’s a no-brainer that she should do those instead of re-reading. But if the teacher didn’t provide any questions? She can still make up her own, but she should leave extra time because doing so will take twice as long.

Footnotes:

(1) Weinstein, Y., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L. (2010). A comparison of study strategies for passages: Re-reading, answering questions, and generating questions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 16, 308-316.